Comparison of mean systemic pressure in patients with acute circulatory failure receiving passive leg raising vs. pneumatic leg compression.

Mean systemic pressure between PLR and PC

Keywords:

Mean systemic pressure, Cardiac output, Venous returnAbstract

Background: Driving pressure of venous return (VR) is determined by a pressure gradient between mean systemic pressure (Pms) and central venous pressure (CVP). While passive leg raising (PLR) and pneumatic leg compression PC (PC) can increase VR, no study has explored the effects of these two procedures on Pms and VR-related hemodynamic variables.

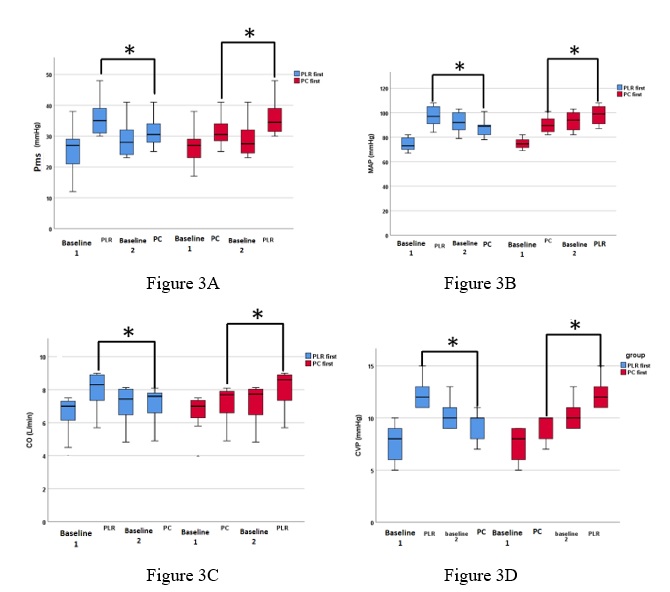

Methods: Forty patients with acute circulatory failure were enrolled in this analysis. All patients obtained both PLR and PC, and were measured for Pms, CVP, mean arterial pressure (MAP), cardiac output (CO), VR resistance (RVR), and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) at baseline and immediately after procedures. To minimize carry over effect, the patients were divided in 2 groups based on procedure sequence which were 1) patients receiving PLR first then PC (PLR-first), and 2) patients receiving PC first then PLR (PC-first). Both groups waited for a washout period before performing the 2 second procedure. Primary outcome was difference in Pms between PLR and PC procedures. Secondary outcome were differences in CVP, MAP, CO, RVR, and SVR between PLR and PC procedures.

Results: No difference was found in baseline characteristics and no carry over effect was observed between the 2 groups of patients. Compared with baseline, both PLR and PC significantly increased Pms, CVP, MAP, and CO. PLR increased Pms (9.0±2.3 vs 4.8±1.7 mmHg, p<0.001), CVP (4.5±1.2 vs. 1.6±0.7 mmHg, p<0.001), MAP (22.5±5.6 vs. 14.4±5.0 mmHg, p<0.001), and CO (1.5±0.5 vs. 0.5±0.2 L/min, p<0.001) more than PC. However, PC, also significantly increased RVR (16 ± 27.2 dyn.s/cm5, p=0.001) and SVR (78.4 ± 7.2 dyn.s/cm5, p<0.001) but no difference in PLR group.

Conclusion: Among patients with acute circulatory failure, PLR increased Pms, CVP, MAP, and CO more than PC.

Downloads

References

Maas JJ, Geerts BF, van den Berg PC, Michael R Pinsky, Jos R C Jansen. Assessment of venous return curve and Pms in postoperative cardiac surgery patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:912–918.

Bayliss WM, Starling EH. Observations on venous pressures and their relationship to capillary pressures. J Physiol. 1894;16:159–318.

Monnet X, Jabot J, Maizel J, Christian Richard, Jean-Louis Teboul. Norepinephrine increases cardiac preload and reduces preload dependency assessed by passive leg raising in septic shock patients. Crit Care Med. 2011; 39:689–694.

Keller G, Desebbe O, Benard M, Bouchet JB, Lehot JJ. Bedside assessment of PLR effects on venous return. J Clin Monit Comput 2011;25:257–63.

Maas JJ, Geerts BF, Jansen JR. Evaluation of mean systemic filling pressure from pulse contour cardiac output and central venous pressure. J Clin Monit Comput. 2011;25:193–201.

Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304-377.

Chen AH, Frangos SG, Kilaru S, Sumpio BE. Pneumatic leg compression devices-physiological mechanisms of action. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2001;21:383-92.

Zadeh FJ, Alqozat M, Zadeh RA. Sequential compression pump effect on hypotension due to spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: a double blind clinical trial. Electron Physician. 2017;9: 4419–4424.

Christopher RL, Evi K, Mustapha A, George G. Pneumatic compression reduces calf volume and augments the VR. Phlebology. 2015;30:316–322.

Mitchell M. levy, Laura E. Evans, Andrew Rhodes. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Bundle:2018 update. Intensive Care med.2018;44:925-928.

Lateef F, Kelvin T. Military anti-shock garment. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2008;1:63-9.