Effect of sepsis protocol in inpatient departments triggered by Ramathibodi Early Warning Score (REWS) on treatment processes

Sepsis protocol in inpatients triggered by Early Warning Score

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.54205/ccc.v31.263852Keywords:

Sepsis, Sepsis protocol, Implementation protocol, Antibiotics, Lactate measurement, Fluid managementAbstract

Background: Sepsis needs to be more focused on the effect of patient management at the ward level. We aimed to evaluate the effect of implementing the sepsis protocol triggered by the Ramathibodi Early Warning Score (REWS) on treatment processes in inpatients with new-onset sepsis.

Methods: We conducted a prospective observational study among adult medical patients admitted to the general wards. A 25-month pre-protocol period was assigned as a control, and a 14-month protocol period was allocated to a protocol group. An inpatient sepsis protocol comprised a nurse-initiated sepsis protocol with REWS ≥2 plus suspected infection, prompt antibiotic, lactate measurement, and fluid resuscitation. Primary outcomes were the achievement of sepsis treatment processes, including the resuscitation and management bundle, namely: 1) the percentage of patients who were taken for the initial laboratory workup for sepsis, especially lactate and blood culture taking before antibiotics; 2) the percentage of patients who received appropriate antibiotics; 3) the percentage of patients who received optimal fluid resuscitation and management; 4) the percentage of patients who performed inferior vena cava ultrasound; 5) the percentage of patients who received steroid and vasopressor drugs; 6) "time-to-antibiotic," the duration from diagnosis of sepsis to receiving antibiotic treatment; 7) "time-to-optimal intravenous fluid management;" 8) "time-to-transfer to ICU.

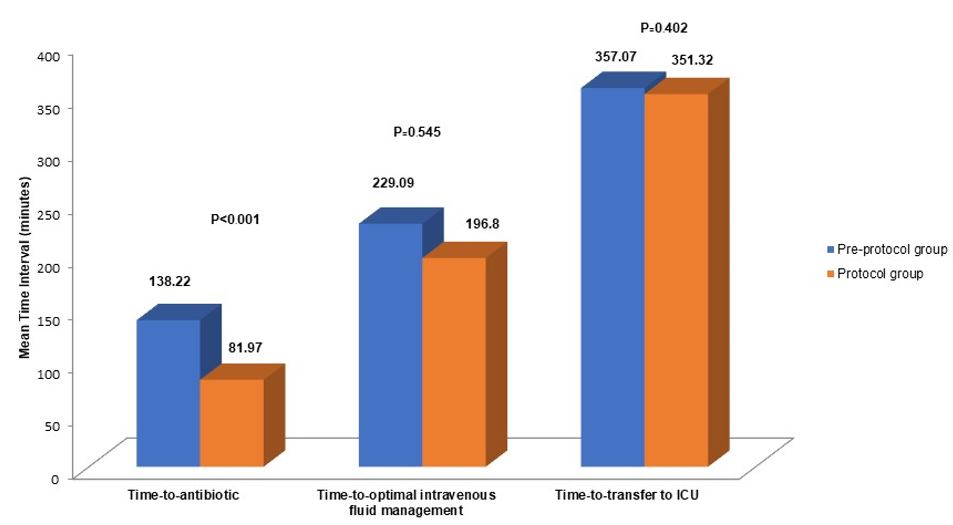

Results: 282 patients were evaluated (141 pre-implementation, 141 post-implementation); 94.7% of patients with sepsis had REWS ≥2. More patients in the protocol period had a lactate measurement and fluid management (89 [63.1%] vs. 44 patients [31.2%], p<0.001 and (50 [35.4%] vs. 22 patients [15.6%], p<0.001, respectively). More patients in the protocol period received antibiotics within 1 hour than in the pre-protocol period (80 [56.7%] vs. 53 patients [37.6%], p=0.001). The time to antibiotic treatment (mean, SD) in the protocol period was shorter than that in the pre-protocol period (81.7 [77.86] vs. 138.22 [145.17], p=0.007). The length of the intensive care unit (ICU) stay was shorter in the protocol period (8 d [3, 16.5] vs. 10 d [5, 20.5], p=0.011). The two groups did not differ in in-hospital mortality, length of hospital stay, or time-to-transfer to the ICU.

Conclusions: Implementing an in-hospital sepsis protocol was associated with significant improvement in sepsis treatment processes, namely lactate measurement, starting antibiotic treatment within 1 hour, fluid management, and a shorter length of ICU stay.

Downloads

References

Gao F, Melody T, Daniels DF, Giles S, Fox S. The impact of compliance with 6-hour and 24-hour sepsis bundles on hospital mortality in patients with severe sepsis: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2005;9:R764-70.

Lee WK, Kim HY, Lee J, Koh SO, Kim JM, Na S. Protocol-Based Resuscitation for Septic Shock: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials and Observational Studies. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:1260-70.

Levy MM, Evans LE, Rhodes A. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Bundle: 2018 update. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:925-8.

Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:486-552.

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest 1992;101:1644-55.

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250-6.

Sutherasan Y, Theerawit P, Suporn A, Nongnuch A, Phanachet P, Kositchaiwat C. The impact of introducing the early warning scoring system and protocol on clinical outcomes in tertiary referral university hospital. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018;14:2089-95.

Sb CH, Browner W, Grady D, Newman T. Designing clinical research: an epidemiologic approach. 2013.

Fleiss JL, Tytun A, Ury HKJB. A simple approximation for calculating sample sizes for comparing independent proportions. 1980:343-6.

Nguyen HB, Corbett SW, Steele R, Banta J, Clark RT, Hayes SR, et al. Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1105-12.

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-10.

Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, Sokol S, Pettit N, Howell MD, et al. Quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, and Early Warning Scores for Detecting Clinical Deterioration in Infected Patients outside the Intensive Care Unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:906-11.

Suttapanit K, Dangprasert K, Sanguanwit P, Supatanakij P. The Ramathibodi early warning score as a sepsis screening tool does not reduce the timing of antibiotic administration. Int J Emerg Med. 2022;15:18.

Rudd KE, Seymour CW, Aluisio AR, Augustin ME, Bagenda DS, Beane A, et al. Association of the Quick Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) Score With Excess Hospital Mortality in Adults With Suspected Infection in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA. 2018;319:2202-11.

Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Brunkhorst FM, Rea TD, Scherag A, et al. Assessment of Clinical Criteria for Sepsis: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:762-74.

Gurnani PK, Patel GP, Crank CW, Vais D, Lateef O, Akimov S, et al. Impact of the implementation of a sepsis protocol for the management of fluid-refractory septic shock: A single-center, before-and-after study. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1285-93.

Ferrer R, Artigas A, Levy MM, Blanco J, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Garnacho-Montero J, et al. Improvement in process of care and outcome after a multicenter severe sepsis educational program in Spain. JAMA. 2008;299:2294-303.

Garcia-Lopez L, Grau-Cerrato S, de Frutos-Soto A, Bobillo-De Lamo F, Citores-Gonzalez R, Diez-Gutierrez F, et al. Impact of the implementation of a Sepsis Code hospital protocol in antibiotic prescription and clinical outcomes in an intensive care unit. Med Intensiva. 2017;41:12-20.

Tromp M, Tjan DH, van Zanten AR, Gielen-Wijffels SE, Goekoop GJ, van den Boogaard M, et al. The effects of implementation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in the Netherlands. Neth J Med. 2011;69:292-8.

Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, Townsend SR, Schorr CA, Beale R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1623-33.

Choi S, Son J, Oh DK, Huh JW, Lim CM, Hong SB. Rapid Response System Improves Sepsis Bundle Compliances and Survival in Hospital Wards for 10 Years. J Clin Med. 2021;10.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 The Thai Society of Critical Care Medicine

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.