Occupational Post-exposure Prophylaxis after Blood and Body Fluids Exposure among Healthcare Workers in Siriraj Hospital

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.33192/Smj.2022.93Keywords:

Healthcare worker, Occupational post-exposure prophylaxis, antiretroviral drugs, HIV preventionAbstract

Objective: The present study aimed to describe the characteristics of occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens and occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (oPEP) in Siriraj Hospital.

Materials and Methods: A descriptive, retrospective cohort study was performed of healthcare workers (HCWs) who had experienced occupational injury in Siriraj Hospital in 2015. Data were extracted from the hospital database.

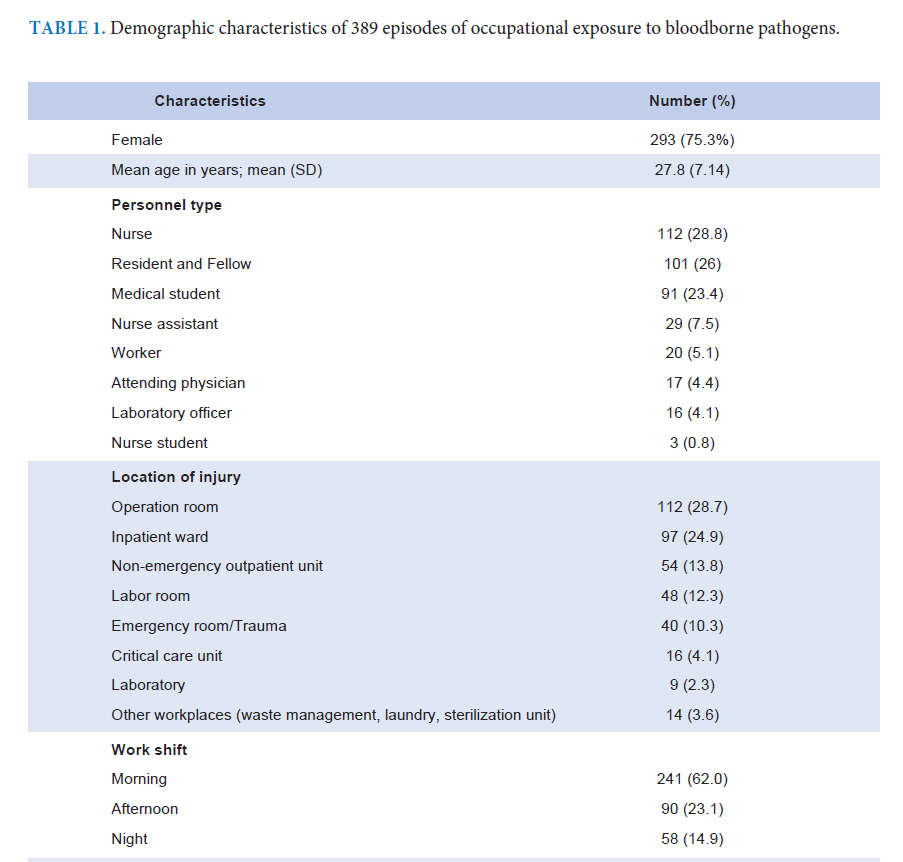

Results: In total, 389 injury episodes were described; of which 293 (75.3%) involved female staff, and 112 (28.8%) involved nurses. The highest number of accidents (112, 28.8%) occurred in the operation room. Needlestick injury (210, 54%) was the most common injury. Overall, 94 (24.1%) HCWs received oPEP; 67 (71.2%) events carried a risk of HIV acquisition, and in 27 (28.7%) cases, the patients decided to take oPEP. Common oPEP regimens were TDF/XTC/LPV/r (33, 35.1%) and TDF/XTC/RPV (32, 34%). Nearly half of the HCWs who received an LPV/r-based oPEP regimen had gastrointestinal intolerance and switched to second-line regimens. Among those who received oPEP, 52 (77.6%) returned at 1 month and 26 (38.8%) returned at 3 months after exposure for a serology test. There was no seroconversion in this cohort.

Conclusion: Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens is a common and increasing risk of infection among HCWs. oPEP with effective antiretroviral drugs within 72 hours after exposure is the main strategy for HIV prevention. The selection of an oPEP regimen with less toxic pills should be considered for efficacy, safety, and adherence. Interventions such as a tracking system or message reminders should be implemented to improve the follow-up rate among HCWs.

References

Zhang MX, Yu Y. A study of the psychological impact of sharps injuries on health care workers in China. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(2):186-7.

Lee JM, Botteman MF, Xanthakos N, Nicklasson L. Needlestick injuries in the United States. Epidemiologic, economic, and quality of life issues. AAOHN J. 2005;53(3):117-33.

Danchaivijitr S, Kachintorn K, Sangkard K. Needlesticks and cuts with sharp objects in Siriraj Hospital 1992. J Med Assoc Thai. 1995;78 Suppl 2:S108-11.

Pungpapong S, Phanuphak P, Pungpapong K, Ruxrungtham K. The risk of occupational HIV exposure among Thai healthcare workers. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999;30(3):496-503.

Hiransuthikul N, Tanthitippong A, Jiamjarasrangsi W. Occupational exposures among nurses and housekeeping personnel in King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89 Suppl 3:S140-9.

Wnuk AM. Occupational exposure to HIV infection in health care workers. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9(5):CR197-200.

Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, Srivastava PU, Marcus R, Abiteboul D, et al. A case-control study of HIV seroconversion in health care workers after percutaneous exposure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

Center for Disease Control. Updated U.S. Public Health Service Guidelines for the Management of Occupational Exposures to HBV, HCV, and HIV and Recommendations for Postexposure Prophylaxis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-11):1-52.

Occupational and non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxi for HIV infection (HIV-PEP): Joint ILO/WHO Technical Meeting for the Development of Policy and Guidelines: summary report2005. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/--ilo_aids/documents/publication/wcms_116563.pdf.

Chaiwarith R, Ngamsrikam T, Fupinwong S, Sirisanthana T. Occupational exposure to blood and body fluids among healthcare workers in a teaching hospital: an experience from northern Thailand. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2013;66(2):121-5.

Kiertiburanakul S, Wannaying B, Tonsuttakul S, Kehachindawat P, Apivanich S, Somsakul S, et al. Use of HIV Postexposure Prophylaxis in healthcare workers after occupational exposure: a Thai university hospital setting. J Med Assoc Thai. 2006;89(7):974-8.

Wilburn SQ, Eijkemans G. Preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: a WHO-ICN collaboration. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004;10(4):451-6.

Frijstein G, Hortensius J, Zaaijer HL. Needlestick injuries and infectious patients in a major academic medical centre from 2003 to 2010. Neth J Med. 2011;69(10):465-8.

Liyanage IK, Caldera T, Rwma R, Liyange CK, De Silva P, Karunathilake IM. Sharps injuries among medical students in the Faculty of Medicine, Colombo, Sri Lanka. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012;25(3):275-80.

Panichyawat N LT. The incidence of needlestick injuries during perineorrhaphy and attitudes toward occurrence reports among medical students. Siriraj Medical Journal. 2016;68:209-17.

Tetteh RA, Nartey ET, Lartey M, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Leufkens HG, Nortey PA, et al. Adverse events and adherence to HIV post-exposure prophylaxis: a cohort study at the Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:573.

Lee LM, Henderson DK. Tolerability of postexposure antiretroviral prophylaxis for occupational exposures to HIV. Drug Saf. 2001; 24(8):587-97.

Wang SA, Panlilio AL, Doi PA, White AD, Stek M, Jr., Saah A. Experience of healthcare workers taking postexposure prophylaxis after occupational HIV exposures: findings of the HIV Postexposure Prophylaxis Registry. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(12):780-5.

Hiransuthikul N, Hiransuthikul P, Kanasuk Y. Human immunodeficiency virus postexposure prophylaxis for occupational exposure in a medical school hospital in Thailand. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67(4):344-9.

Ruxrungtham K CK, Chetchotisakd P, Chariyalertsak S, Kiertburanakul S, Putacharoen O, et al. Thailand National Guidelines on HIV/AIDS Treatment and Prevention 2021/2022. Nonthaburi: Division of AIDS and STIs, Department of Disease Control; 2022.

Cresswell F, Asanati K, Bhagani S, Boffito M, Delpech V, Ellis J, et al. UK guideline for the use of HIV post-exposure prophylaxis

HIV Med. 2022;23(5):494-545.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following conditions:

Copyright Transfer

In submitting a manuscript, the authors acknowledge that the work will become the copyrighted property of Siriraj Medical Journal upon publication.

License

Articles are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows for the sharing of the work for non-commercial purposes with proper attribution to the authors and the journal. However, it does not permit modifications or the creation of derivative works.

Sharing and Access

Authors are encouraged to share their article on their personal or institutional websites and through other non-commercial platforms. Doing so can increase readership and citations.